This week is Holy Week for Christians who follow the Gregorian Calendar. Officially, Japan counts years with “eras” beginning anew with each emperor (much like ancient Israel, the Mayans, etc., when they said “in the fourth year of king so-and-so”). 2022, for example, is 令和 (Reiwa) 4. But just as America’s “customary units” of pounds and miles are actually just conversions from underlying meters and kilograms anymore, so is the Japanese calendar fundamentally Western. Instead of A.D. (or C.E., Common Era), for example, Japanese texts often use 西暦 (seireki, “Western Reckoning”).

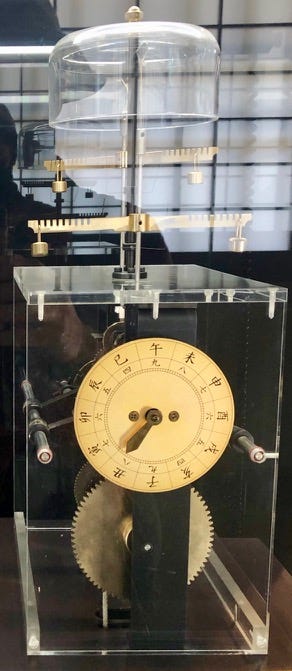

Before the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Japan followed a modified version of the Chinese lunisolar calendar, which we still hear something about when Chinese New Year comes around, interrupting supply chains everywhere. Since 1873, however, Japan has followed Pope Gregory’s 1582 decree.

This adaptation extends well beyond the mere numbering of years. One of my first thrills of learning kanji came when I started recognizing the days of the week: 日, 月, 火, 水, 木, 金, 土 (Sunday through Saturday). As readers likely know, English/German days of the week are named for ancient gods, some of which are translations of the underlying Roman gods into Old English/Norse. These pagan European gods have now been imported into the Japanese days of the week: 日, Sun, Sunday; 月, Moon, Monday; 火, Mars (Týr), Tuesday; 水, Mercury (Woden/Odin), Wednesday; 木, Jupiter (Thor), Thursday; 金, Venus (Frigg/Freyja), Friday; 土, Saturn, Saturday. They also refer to the corresponding heavenly bodies.

All of which means that the reckoning of the year is, in its own strange way, a confession of Christian faith. The whole official world runs itself implicitly around the (erroneous) date of Christ’s birth, as decreed by the aforementioned pope. So even here in Japan, a thoroughly secular country with no presence of Christendom, it is the Christian calendar that reigns, seireki more significant than imperial year in most cases.

Which brings me to a point that cannot be made often enough: Bach’s music is no longer “Western.” Just as with the way Japan has counted its days, months, and years for a century and a half, “Western music” has gradually become natively Japanese. I will be expanding on this theme over the next few weeks as I engage with the work of Thomas Cressy, currently a doctoral candidate at Cornell University, whose work promises to be the definitive statement on the origins of Bach reception in Japan.

This means, of course, a break with the dominant postcolonial discourse, which has never accurately applied to Japan anyway. It also demands a reengagement with Bach’s own musico-theological language. For in engaging deeply with Bach, Japan’s musicians and aficionados have also encountered the eighteenth-century composer’s deep Lutheran piety. As with so many things Japanese, it has long sat in silence. But just as time itself has been bent to Christ’s birth, so is Bach’s “pure music” filled with transcendent significance.