“Bach’s the Best,” I proposed in a recent reflection, as perhaps the most straightforward answer to the question, “Why is Bach so revered in Japan?” Here I suggest a parallel explanation based on a phrase I have heard time and again in my conversations and research. In Japan, Bach is “The Father of Music.”

Elsewhere there seem to be many competitors for the title. For the biblically-minded, music’s father is usually named as Cain’s descendant Jubal (whose name may share a similar onomatopoeic Proto-Indo-European root for “exclamation of joy” as our Greek—>Latin—>French-derived “jubilee”). Genesis 4:2 claims Jubal “was the father of all those who play the lyre and pipe.”

Interestingly, in this genealogical, developmental account, music is clearly seen within the scope of other technologies: Jubal’s brother dwelt in tents, and his cousin, Tubal-cain, forged “all instruments of bronze and iron.” Music is sandwiched between fundamental technologies and clever craft, somewhere between shelter and tools.

For the mythologically-minded, the “Father of Music” is Pan, who invented the pipes that bear his name; or Mercury, who (mockingly) made a tortoise shell into a lyre.

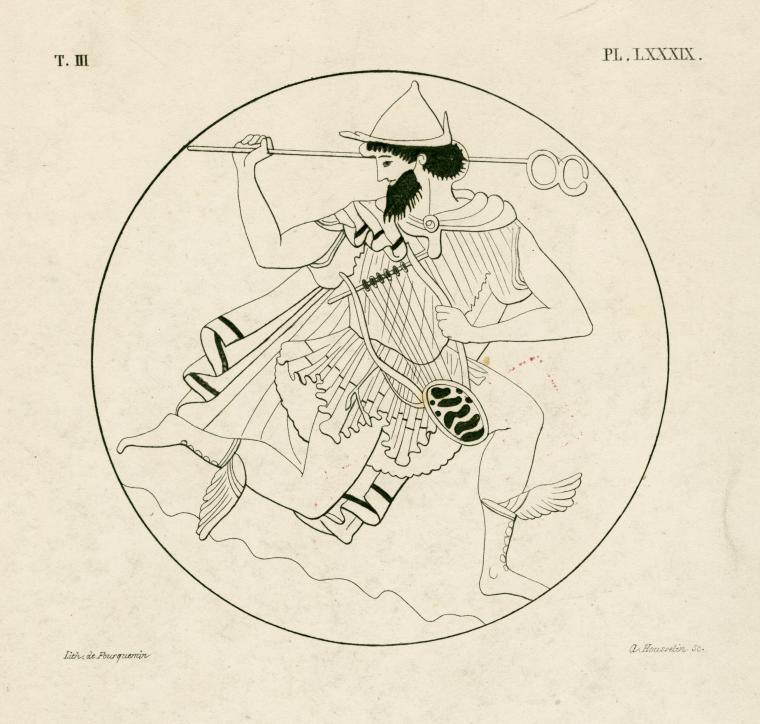

For mathematicians (and historians of music theory), Pythagoras fits the bill. He may rather be the father of harmonics, for Pythagoras appreciated music for the vibrations and ratios it created. The resulting tones and overtones pulsate through the entire universe, bringing us into mystical harmony with the music of the spheres. His scale is the basis for Western music.

Some have even applied the sobriquet “father of music” to Bob Marley, for profound reasons, I’m sure.

The Japanese are hardly the first to apply this title to Bach. Beethoven, apparently, called Old Bach the “original father of harmony,” if not the father of music. The phrase seems to have become a commonplace among pedagogues seeking to create a teachable genealogy of Western musicians. Even in India, “Bach” is the answer to the question “Who is the father of music?” on secondary school tests!

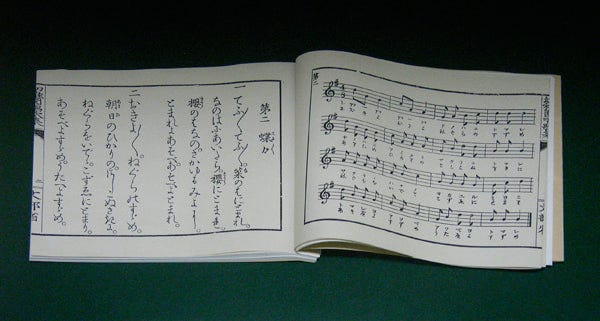

But it seems to have been very early in Japan’s modern encounter with the West that Bach acquired this definitive monopoly as music’s father. Thomas Cressy (whose excellent work I have mined before) has not found a definitive source for the idea, relying upon scholar Tadashi Isoyama's 2012 work on the subject. Cressy does points to the ubiquity of the moniker in Japanese musical publication, including the following 1998 manga.1

The “Father of Music” can also just be a synecdoche for “the best” or “most famous.” Famous Bach appears as a character in the colossal Shuumatsu no Valkyrie: Record of Ragnarok, a mashup of mythologies that occurs at a millennial counsel of the gods, where they let condemned humanity fight divinity to decided their fate.

In a volume that features Adam, Odin, Mozart, Brunhilde, Shiva, and Zeus, the spirit of Bach is brought to tears by Hermes’s rendition of “Air on the G-String” (BWV 1068), played to announce the battle between Adam and Zeus. Don’t try to make too much sense of it. But Bach’s right there among the gods.

Bach’s godly status may have something to do with Luther Whiting Mason, former student of distant relative and discoverer of the Neumeister Collection of chorale preludes, Lowell Mason (also here). Both Masons were eminent educators, and it seems quite probable that Luther Whiting brought Bach along in his pedagogical plans when he was invited by the Ministry of Education to revamp music for Japan’s elementary and middle schools. He taught the first generation of Japan’s music educators, was a primary force behind the first Western musical textbook (Shōgaku shōka-shū, 小學唱歌集, also here and here), and pioneered keyboard instruction (including Bach) during his three-year stay (1880–1882).

The renowned conductor Helmut Rilling, for his part, in an interview in Gramophone, points to Bach’s durability: “He was the great consolidator, summing up the best of what had gone before, refining the best ideas of his own time… He’s the teacher par excellence… His music has influenced every later generation of composers and musicians—a heritage that continues right up to our own time.”

We sensitive Westerners are currently primed to take offense that one of “our” own has “colonized” foreign territory and usurped a place that somehow ought to go to someone indigenous. That’s not how it’s seen in Japan. “The Father of Music” does not seem to be an exclusive category.

In the simplest sense: Bach is great, perhaps the greatest. He comes before, and is thus worthy of our honor and respect. That is what it means to be the “Father of Music.”

Thomas A. Cressy, “The Case of Bach and Japan: Some Concepts and Their Possible Significance,” Understanding Bach 11 (2016): 141, n. 9.